Explorations

Contents: Dionysian Figures in Welty's Fiction | The Burr Conspiracy: Early Schemes in the Southwest | The Harpe Brothers: Terrors on the Trace | Murrell: A Malignant Mastermind | Tech

Dionysian Figures in Welty’s Fiction

Nestled among a plethora of other skillfully executed literary techniques lie the many mythological allusions and symbols in Welty’s fiction. Most, if not all, the stories in The Wide Net reference either mythology or folklore, and such references span across various cultures and subjects. As such, significant scholarly work has been done in the analyzation of her symbols, some of which are still debated by various readers. Welty herself has written about her appreciation for and utilization of myth, though she also cautions readers not to force any of them too directly onto her work (Brower 5, 13). However, interpreting her stories within this framework reveals layers of literary value and adds complexity and depth to her fiction. Since it would prove quite impossible to cover the extent of her use of myth and folklore in one article, this essay will cover the specific role of Dionysian figures in Welty’s stories from The Wide Net.

Dionysian figures are those who exhibit certain traits or fulfill certain roles derived from the Greek god Dionysus (“Dionysian”). Dionysus, also called Bacchus or Liber Pater, was the god of wine, fertility, and ecstasy. He was associated with nature, animals, and wild parties; the Cult of Dionysus would hold elaborate festivals in the god’s honor. These festivals were notorious for involving heavy drinking, excessive revelry, sexual activity, and sometimes brief insanity during which some attendants reportedly were capable of violent acts. Many festivals, especially those referred to as the Bacchanalia, were secretive and attended almost exclusively by women (“Dionysus”). In literature, then, Dionysian figures are characters, usually male, that may reflect such aspects as vigor, nature, drinking, and sexuality. They often appear in relation to animals or exhibit a youthful vitality (“Dionysian”).

Such characters appear three notable times in The Wide Net. In addition, while the titular story does not necessarily contain a strict Dionysian figure, it does contain events that apparently relate to Dionysian fertility rites. “The Wide Net” describes a journey into the natural world, where events like feasts, fights, and challenges take place. These occurrences, combined with the fact that Hazel Jameson is pregnant, denote celebrations of nature, wildness, and vitality (Brower 22).

The first clear Dionysian figure the reader encounters in the collection is Don McInnis in “Asphodel.” Three women, Cora, Phoebe, and Irene, venture into the woods to picnic near the ruins of a mansion that mysteriously burned down. They recount the forced marriage between Sabina, their former employer, and a man called Don McInnis, who Sabina drove away after learning that he cheated on her. At the end, Don McInnis himself appears in the ruins, completely naked and surrounded by goats, which chase the ladies out of the glade.

The Dionysian imagery appears early in the story, and not exclusively in terms of Don McInnis. The food and drink the ladies bring allude to those commonly associated with Dionysus, including grapes and wine (Welty 242). The Dionysian myths involve a cult of women followers, often called maenads, who were susceptible to insane frenzy while worshipping him (Koontz 3-4). The ladies describe McInnis as animalistic, drunken, and having “the wildness we all worshipped” (Welty 243-244). McInnis as Dionysus indicates that Sabina is one of those women driven mad by the god, an allusion reinforced by the fact that her behavior is described by the ladies as often strange and erratic. Also, before she dies, she tears apart letters (248), which could allude to the story of maenads becoming so deranged that they tear apart people and animals (“Dionysus”). The appearance of McInnis at the end of the story matches features that are attributed to images of Dionysus as well. McInnis appears nude and bearded (Welty 249); early Greek depictions often portrayed Dionysus as bearded (Koontz 3), and the nudity corresponds to his attributes of virility and sexuality. The herd of goats that appears corresponds to the satyrs, figures of Greek mythology who were also associated with fertility and were said to follow Dionysus (“Dionysus”). McInnis’s appearance and behavior combined with the natural scenery, goats, and food and drink allude to various aspects of Dionysian myths, making “Asphodel” a prime example of Welty’s utilization of mythology.

The next story in the collection that involves a Dionysian figure is “Livvie.” This story tells how Livvie, a young girl married to a much older man, has been secluded in the woods and takes care of her husband as he nears death. At one point she encounters a young field hand named Cash. His bright, cheery youthfulness catches Livvie’s attention. They go into the house, where Solomon sees them and, right before dying, recognizes that Cash will become Livvie’s new partner.

Cash, through his association with spring, nature, and youthful male vigor, encompasses Dionysian qualities. The story takes place at the beginning of spring, a season associated with masculinity in the story, such as in the line that spring “was as present in the house as a young man would be” (Welty 280). When Cash appears, his colorful clothes are described through comparisons to nature, like his “leaf-green” coat (285). Cash entrances Livvie with his vitality and activeness, and she kisses him even before Solomon’s death (286). At the end, after Solomon has died, they stand together looking outside, where everything shines “with the bursting light of spring” (290). Since Cash is associated with spring, nature, vitality, and even sensuality, he becomes a Dionysian figure that poses a sharp contrast to the old and withered Solomon and indicates a fresh start for Livvie.

The third story, “At the Landing,” features a man named Billy Floyd as the Dionysian figure. In this story, Jenny lives a secluded life with her grandfather, who soon dies. Jenny, no doubt influenced by her feelings of loss and isolation, fixates on Floyd, a man whose origins are unknown and who seems to be just passing through the area. When a flood sweeps through the Landing, Floyd rescues her but then violates her. Jenny still holds on to her strange feelings of love for him, however, and pursues him to the Mississippi River. The story ends with her waiting for him on the bank while the fishermen take turns violating her.

Despite the lyrical tone and beautiful nature descriptions in “At the Landing,” it is a grim, complex story. Floyd encompasses some of the darker aspects of Dionysian myth, such as the influence the god’s inspiration supposedly had on the mental state of his female worshippers (“Dionysus”). In the beginning the character is referred to as “the rude wild Floyd” (Welty 294). He inspires in Jenny a strange fascination that she believes is love for him, although he does nothing to reciprocate this affection. Perhaps their interactions together might be seen as a twisted version of a Dionysian ceremony. Floyd and Jenny interact while immersed in nature, whether in the open field near the cemetery or during the flood. Floyd’s violation, and later the fishermen’s violation, of Jenny could relate to the sexual rituals said to take place at the festivals. Finally, the meal that Jenny and Floyd have after he assaults her could translate to the feasts had at the ceremonies. The story vaguely mentions that Jenny’s mother suffered from a “wild desire” that Jenny’s grandfather saw as “a force of Nature” (293-294), so perhaps Jenny’s fixation on Floyd is not a singular type of incident in her family. Perhaps her mother too was influenced by a Dionysian madness, and the grandfather, much like the men in ancient times who opposed women’s worship of the Greek god, tried to stifle those emotions (“Dionysus”).

Other smaller details point to Floyd as a Dionysian figure as well. For example, Jenny watches him through a tangle of grape vines (Welty 295). Several times throughout the story, Floyd is related to nature and animals. He skillfully and easily rides the horse in the pasture and goes off into the woods, rejoining the wild (297). The old ladies at the Landing say that Floyd “could scent coming things like an animal” (309). Floyd is also associated with the river, a powerful force that corresponds to his connection with nature and his influence over Jenny. In his dream, her grandfather seemed to think that Floyd could predict the river’s floods (291), yet again giving him a mysterious influence over the things around him. Emphasized throughout the story, the combination of Floyd’s deep connection with nature and his strange power over Jenny indicates that Floyd is a well-developed yet troubling Dionysian figure.

As evidenced by the analyses of these stories from The Wide Net, Welty was a master at utilizing mythological elements to take already interesting and complex stories and place them in a larger literary and cultural context through recognizable symbols and allusions. In “Asphodel,” “Livvie,” “At the Landing,” and even a little in “The Wide Net,” Welty explores the idea of the Dionysian figure and how such a character interacts with the people and environments around him. Since these stories also feature questions of sexual and romantic relationships and a profound connection to nature, Dionysian figures serve to further deepen the exploration into these themes. Though the scope of Welty’s mythological allusions is certainly not limited to this subject, her use of the myth of Dionysus and his wild revelries takes the reader on a revealing journey of connections between character, setting, and the ancient stories humans still tell about themselves.

Sources

Brower, Robert Keith. Myths and legends in the stories of Eudora Welty. 1972. University of Richmond, master’s thesis. UR Scholarship Repository.

“Dionysian”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 17 Sep. 1999, www.britannica.com/art/Dionysian. Accessed 8 March 2022.

“Dionysus.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 26 May 2021, www.britannica.com/topic/Dionysus. Accessed 7 March 2022.

Ford, Richard, and Michael Kreyling, editors. Eudora Welty: Stories, Essays & Memoir. The Library of America, 1998.

Koontz, Alana. The Art and Artifacts Associated with the Cult of Dionysus. 2013. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, master’s thesis.

Welty, Eudora. “Asphodel.” Ford and Kreyling, pp. 241-251.

—. “At the Landing.” Ford and Kreyling, pp. 291-312.

—. “Livvie.” Ford and Kreyling, pp. 276-290.

—. “The Wide Net.” Ford and Kreyling, pp. 204-227.

The Burr Conspiracy: Early Schemes in the Southwest

Thanks to today’s popular culture, many people have at least heard of Aaron Burr and his infamous duel with Alexander Hamilton. However, few people are aware of what happened to Burr after that fateful encounter and how he concocted an elaborate, treasonous scheme to capture U.S. territory and create his own country to rule over.

Burr served as a senator in the United States government from 1791 through 1797. He narrowly missed being elected president in 1800 and instead served as vice president under Thomas Jefferson, who served two consecutive terms. On July 11, 1804, after Hamilton thwarted Burr’s attempt to be elected governor of New York, Burr fatally shot Hamilton in a duel. Burr butted heads with both the president and the Republican party and was not placed on the Republican ticket for the next election. Burr had always been ambitious, and he knew that his political prospects were declining, especially after killing Hamilton. It is believed that these frustrations led Burr to begin developing his plans as early as 1804.

The Territory of Louisiana, which the United States gained in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, suffered from unrest. Spain disputed with the U.S. about the borders of the territory, and relations between the two countries were tense. Some believe Burr attempted to use this tension as an excuse, claiming that the government would secretly condone a group of Americans taking charge of land before the country was officially at war with Spain. The Louisiana Territory was also sparsely settled, and a significant portion of those settlers voiced their support for seceding from the United States. Encouraged by these factors, Burr intended to create his own, separate empire by transporting a military force down the Mississippi River and taking over New Orleans and nearby areas. If possible, he would expand farther out and even try to capture some parts of Mexico.

Burr, of course, planned to place himself in charge of this new territory, but to carry out this scheme, he would need lots of help. In April of 1805, Burr toured areas of Kentucky; Tennessee; Missouri; Natchez, Mississippi; and New Orleans, Louisiana, as he gathered a sense of possible support and explored areas important to his plan. General James Wilkinson was one man Burr employed to aid in his endeavors. Wilkinson, Commander-in-Chief of the United States Army, had been friends with Burr since the American Revolution, and Burr helped Wilkinson become the governor of Northern Louisiana. Wilkinson’s position in the army afforded him the advantage to maneuver troops around the territory without much suspicion. Supposedly, he would be Burr’s second-in-command in the new country. However, Burr would soon find out that his trust in Wilkinson was misplaced.

Burr also collaborated with a wealthy Irish immigrant named Harman Blennerhassett, who, accompanied by his wife and children, built a large mansion on an island on the Ohio River. Seeking to utilize Blennerhassett’s wealth and the strategic position of Blennerhassett Island for navigating the river, Burr wrote to him asking to tour the grounds. During his visit, Burr managed to gain Blennerhassett’s support, and the island was fixed as a headquarters for supplies, weapons, and recruits. Burr also appealed several times to Britain, offering to help Britain claim American land in return for money and support. These appeals were never answered.

Soon enough, rumors began to spread both in the east and in more western areas like Kentucky about a conspiracy, one which possibly involved Burr. Burr tried to find the balance between recruiting others for his cause and keeping his designs secret, but elements of his plan were quickly gaining public notice. By 1806, Burr’s scheme began to falter. On October 9, Wilkinson sent a letter to President Jefferson that detailed Burr’s plan. Wilkinson had lost faith in the conspiracy and wanted to get out while he still could. While he did not name Burr specifically, Burr’s name had been so often circulated in relation to possible secret plots that his involvement seemed blatant.

A newspaper in Frankfort, Kentucky, called the “Western World” published a series of articles in 1806 telling of a scheme to betray the United States in favor of Spain. Among the traitors listed were Supreme Court Judge Benjamin Sebastian, Federal Court Judge Harry Innes, Senator John Brown, Wilkinson, and Burr. While some of the details were not completely accurate, much of Burr’s scheme was divulged, creating quite a stir in Kentucky society. On November 3, 1806, Colonel Joseph Hamilton Daveiss, attorney for the U.S., motioned the court of Judge Innes to summon Burr to answer for his conspiracy, which Daveiss accurately relayed to the court. Burr was very popular in Kentucky at the time, and though Daveiss was also respected, most people sided with Burr. Judge Innes overruled Daveiss’ motion, but Burr, after receiving word about the development, came to the court from Lexington and insisted that the motion be approved so the matter could be settled. The parties agreed, and this began a long series of speeches, postponements, and legal maneuvers in which Daveiss fought against the oratory skills of both Burr and his lawyers, Henry Clay and Colonel Allen, as well as public opinion.

On November 25, Jefferson issued a proclamation that warned against and denounced the scheme, but this proclamation did not reach Kentucky until after Burr’s trial. When it did, a law was passed authorizing the seizure of Burr’s boats that had evaded the Ohio militia and were sailing downriver.

Before he agreed to represent Burr, Clay made Burr promise that he indeed was innocent of these claims. Burr promised that he held no schemes in any way harmful to the United States and claimed that he did not even have access to any military weaponry; in reality, his forces were already gathering on Blennerhassett’s Island, and some of his boats were sailing downriver. On December 1, the same day Burr made his promise to Clay, a messenger from President Jefferson informed Ohio’s seat of government of Jefferson’s warning. After the Ohio government passed a law bestowing proper authorization, ten of Burr’s boats were captured on the Muskingum River. The boats, carrying supplies, were on their way to the Ohio River. However, this event also occurred without the Frankfort court’s knowledge, and the court ultimately acquitted Burr. He left Frankfort for Nashville, Tennessee, on December 7, 1806.

While Burr had evaded the law, his boats and supplies did not. The Ohio militia captured a considerable amount of Burr’s boats and supplies at a boatyard in Marietta, a town near Blennerhassett Island, on December 9. Two days later, the militia landed at Blennerhassett’s Island. Though most of the recruits escaped, the outpost was ruined, and Blennerhassett’s mansion was pillaged.

Around the end of December, Burr reunited with Blennerhassett on the Ohio River. He found that his military force was only a group of less than one hundred men—he had expected thousands to join his cause—but he decided to press on, trying to pick up more people as they travelled by boat down the Mississippi River. Burr arrived at Bayou Pierre in January 1807, accompanied by almost 60 followers.

In June 1788, the Bruin family of Virginia came to the old Natchez District, where Spain had control and was encouraging settlement by bestowing large amounts of land to settlers. The Bruins settled at the mouth of the Bayou Pierre, a minor tributary of the Lower Mississippi River. Their establishment grew and was frequently visited by river travelers; the settlement would develop into the town of Bruinsburg. Peter Bryan Bruin, the son of Bryan Bruin, would become one of the first territorial judges for the United States for the Mississippi Territory.

Burr met with Judge Bruin, who informed him that the militia was looking for him. A reward had been offered for his capture, and eight U.S. gunboats were sailing from New Orleans. Additionally, the newspapers contained a complete, translated copy of the Cipher Letter, an incriminating coded letter Burr had sent to Wilkinson detailing all his plans, including important dates and locations for the mobilization of their forces. Considering his opposition, Burr surrendered to the authorities. Brought before the grand jury, Burr claimed that he had no plans of seizing U.S. territory—at points he protested that he was just trying to establish a settlement on some of his land located in Louisiana’s Ouachita River Basin. The jury did not indict Burr, but one of the two judges presiding over the case wanted Burr to return to the court. Burr seized an opportunity and escaped into the wilderness, but soldiers soon captured him on February 13, 1807, near a hamlet called Wakefield in Louisiana. The soldiers returned a very disheveled Burr to the federal court in Richmond, Virginia. The Cipher Letter figured prominently when he stood trial for treason and was used by both the defense and prosecution. General Wilkinson himself was also utilized as a witness against Burr. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall, however, depended on a strict interpretation of the Constitution’s definition of treason. He decided that Burr’s actions did not meet this definition; once again, Burr was acquitted.

Burr’s reputation suffered greatly from these incidents, and public opinion turned heartily against him, with some states accusing him of their own charges. Fearing for his life, Burr moved to Europe. Ever persistent, he continued his attempts to entice Britain as well as France to invade the United States, but these attempts also were unsuccessful. Burr returned to the United States four years later, when the War of 1812 loomed on the horizon and Burr’s earlier exploits had faded away in light of these more recent tensions. He became an attorney in New York and practiced law there with relative success. Burr died in 1836, and his grand, ambitious, treasonous dreams of building his own empire from stolen land died with him.

Sources

Bragg, Marion. Historic Names and Places on the Lower Mississippi River. Mississippi River Commission, 1977.

“The Burr Conspiracy.” PBS, www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/duel-burr-conspiracy/

The Harpe Brothers: Terrors on the Trace

Note: The following account comes from the book The Outlaw Years by Robert M. Coates. His record of the lives of the outlaws and the events surrounding the Trace is not a complete, infallible account given his artistic embellishments, more recent discoveries, and the difficulty of distinguishing historical fact from folklore. However, the book holds much significance since Eudora Welty used it as a reference for her stories, and thus the information within it is valuable not only for its historical account but also for its usefulness in examining her writing.

Trail of Blood

Born in approximately 1768 and 1770, respectively, the Harpes’ exact heritage is uncertain. Many believed Micajah “Big Harpe” and Wiley “Little Harpe” were brothers (24), and even though some accounts today report they were actually cousins, they were known together as the Harpe brothers. The Harpe brothers left North Carolina in 1795 and headed west, along with two women, the sisters Susan and Betsey Roberts. Supposedly, Susan was lawfully married to Big Harpe. She had dark hair and was gaunt, while Betsey had blonde hair and a brighter disposition; Betsey was, for lack of a better term, “shared” between the Harpes (25).

In April 1797, a circuit rider for the Methodist Church named William Lambuth rode westward along the Wilderness Road (21). He was held up by the Harpe brothers, who robbed him at gunpoint. This Harpe robbery was unique, as it was their first recorded crime and one of the few that did not involve them murdering someone (24).

The Harpes moved to Knoxville not long after they robbed Lambuth. They settled on a piece of land to the west of Knoxville, on Beaver Creek. Little Harpe met and married Sally Rice, daughter of John Rice, a minister (25-28).

Their crime spree began with petty theft. A butcher they sold pork to in Knoxville, John Miller, observed that they were selling him increasing amounts of pork; it seems they were stealing pigs, even as they were raising hogs of their own. They engaged in other rowdy activities, like heavy drinking, gambling, racing, betting, etc. Their neighbors began to mistrust them, and when fires destroyed some of their buildings, they mistrusted the Harpes even more. After being accused of stealing a team of horses and chased by a posse, the Harpes escaped into the forest (28-30).

The Harpes’ next crime took place at a notoriously shady tavern, run by a man named Hughes, on the banks of the Holston River a few miles outside of Knoxville. On the night the Harpes visited, a man named Johnson was in the tavern. Not much is known about Johnson, but two days later his body was found floating in the river. The body had been ripped open, and its insides had been replaced with stones in attempt to weigh it down. The Harpes had vanished (30-32).

This incident began a series of murderous crimes attributed to the Harpes. They moved around the Trace, killing and robbing without much discretion, towing the women along with them. After a man from Virginia named Stephen Langford was found murdered at the bottom of a ravine, suspicion once again fell on the Harpe brothers. A posse from Stanford soon caught up to the Harpe group, who did not resist arrest and were taken to the town to stand trial (35).

At the trial, the group claimed the name Roberts, except for Betsey who called herself Elizabeth Waker. They were sent to jail until they could be taken to Danville for a trial at the District Court (35). During this time, all three of the women with the Harpes were pregnant and nearing delivery, an added worry for John Biegler, the warden at the Danville District Jail. Despite his precautions to add extra security to the jail, the brothers escaped anyway around March 16. They left the women behind, who by then had all given birth (36-37).

Posses, with many of the men seeking to take justice into their own hands, set out in search of the Harpes. At one point, a posse ran into the Harpes, who stared at them intimidatingly before both groups ran off in opposite directions (37-38). This instance was only one of several in which a posse gave in to fear when faced with the menacing brothers.

In Danville, the three women that had accompanied the Harpes were put on trial. However, their state, especially being new mothers, garnered enough sympathy to have them acquitted. For some unknown reason, perhaps out of fear, Susan, Betsey, and Sally returned with their children to the Harpe brothers (39-40).

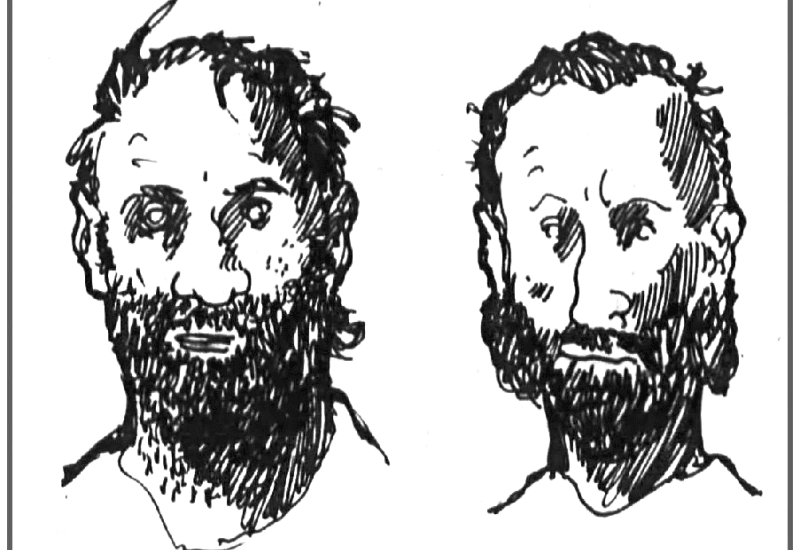

Outcasts Among Outlaws

The Harpes appeared to be moving northwest toward the Ohio and the Mississippi Rivers. More men joined posses looking for the Harpes, and the State of Kentucky offered three hundred dollars for Micajah and three hundred for Wiley Harpe to anyone who could return them to the Danville District Jail. Descriptions of the Harpe brothers were also published. Micajah’s description characterized him as in his early thirties, robust, wearing a grim expression, and six feet tall with short black hair. He was last seen wearing a striped nankeen (yellow cotton cloth) coat, blue wool stockings, leggings, and nankeen trousers. Wiley is described as having the same grimness about him, but with straighter short black hair, a thinner face, and looking to be the older brother despite being younger than Micajah. He was seen wearing a coat similar to Micajah’s as well as an overcoat, dark blue wool stockings, and leggings (41-42).

As the posses and men posted as lookouts searched unsuccessfully for the Harpes, they rounded up other criminals, resulting in a widespread clean-up of the territory. Posses, groups of Regulators, and others destroyed liquor stores and brothels, even taking the law into their own hands by hanging at least fifteen people, whipping, beating, and driving wrongdoers out of the territory. Those who escaped moved further west or north to the Mississippi River and the unsettled areas along the Ohio River. By the end of this clean-up, the Harpes remained uncaptured (42-43).

The Harpes fled to Cave-In-Rock, a popular outlaw hideout, where the three women were waiting for them. At first, upon arriving and engaging in the activities of the river pirates, they fit in with the violent atmosphere. Most outlaws, when they robbed a traveler, killed the person so he could not spread word of their crimes in nearby settlements. However, the enthusiasm with which the Harpes carried out violence and the horrid acts of torture they committed on their victims soon disgusted even their fellow outlaws. The outlaw gang finally had too much and drove the Harpes and their wives and children out of the area (50-53).

At this time, the Harpes began posing as people hunting for the Harpes. They inquired for news of their whereabouts and pretended to be attempting to follow the Harpes’ trail. The Harpes also posed as Methodist preachers traveling to their congregation, and they even had the proper attire (58). They came dressed as preachers to James Tompkins’s cabin, located at the point where the Red Bank to Nashville trail crossed the Barrens of the Tradewater Creek. Tompkins invited them in to dine with him and his family, and Big Harpe even said grace over the food (58). When Tompkins wondered at how much the “preachers” were armed, they claimed that they were protecting themselves from the Harpes. Tompkins then mentioned that he did not have much powder, and Big Harpe gave him some from his powder-horn. The Harpes, dedicated to their characters, blessed the cabin before they left (59).

Sinister Company

On the night of July 20, 1799, the Harpes arrived at the cabin of Moses Steigal. The connection between the brothers and the Steigals is not completely known. Steigal already had a questionable reputation among his fellow settlers, and it seems he knew the Harpes and had dealt with them before. Steigal was not home yet on the night the Harpes arrived, but Mrs. Steigal was, along with a surveyor named Major William Love. Mrs. Steigal, who supposedly knew the Harpes but had been told by her husband to keep their identity secret, introduced the brothers as preachers to Love, who was there to see Mr. Steigal about business. That night, the Harpes murdered Love, Mrs. Steigal, and her baby. When Mr. Steigal returned home, he found his house on fire as well. The Harpes had fled, and during their escape they killed Gilmore and Hudgens, two men who ran into the brothers on the trail (59-62).

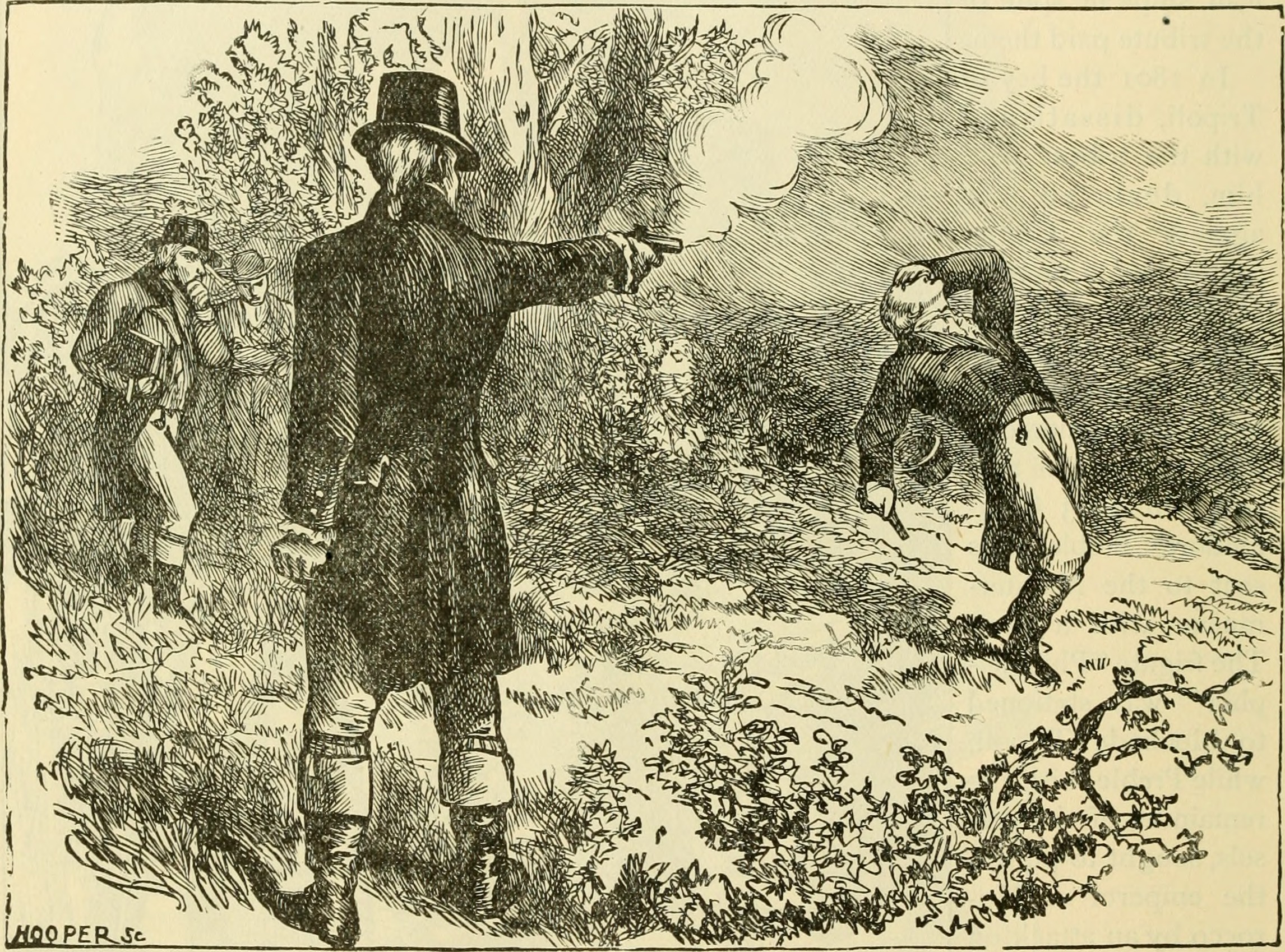

The burning cabin caught the attention of Steigal’s neighbors. Squire McBee, Samuel Leiper, James Tompkins, and John Williams formed a posse with an enraged Steigal. They did not pack many provisions and underestimated how long the search would take, but Steigal pushed them to keep going. A couple days after they began their search, the posse spotted the Harpes, plus the women and their children, grouped together in a valley. Standing at the side of a trail, the Harpes appeared to be readying to kill a traveler they had stopped, but the noises and shots from the posse alerted them. The Harpes mounted their horses, leaving the women. Little Harpe vanished into a thicket, but the posse followed Big Harpe as he continued down the Trace. The riders had to pass over hills, and at the top of the second Samuel Leiper fired his rifle at Big Harpe, but the shot apparently missed. His ramrod malfunctioned, and he could not reload his gun correctly, so Tompkins gave him his gun—the same gun he had filled with the powder Big Harpe had given him while posing as a preacher (62-63).

Using Tompkins’ gun, Leiper fired again and hit Big Harpe in the spine. Big Harpe led his horse into the thicket, still followed by the posse. They found him on the brink of unconsciousness in his saddle. Leiper and Tompkins, who had taken the lead of the posse, pulled him off his horse and laid him on the ground, waiting for the others to catch up. When Steigal arrived on the scene, he kicked Harpe and threatened to cut his head off with his knife. The other members of the posse restrained him and decided that Harpe would either die there or live long enough to be brought back to town to stand trial (64).

Big Harpe was slowly dying. As he lay on the ground, he spoke of his crimes, saying that he regretted none of them except one in which he smashed Susan’s baby against a tree and then threw it into the woods when he became infuriated at its crying. He also claimed that it was God’s intention that he commit his crimes. Steigal, meanwhile, grew even more impatient. He toyed with Harpe by pointing his rifle at him and taunting him (65).

Then, supposedly while Harpe was still alive and conscious (though reports vary), Steigal used Harpe’s own knife to cut off his head. Steigal put the head in a bag, leaving the rest of the body in the woods (66).

At the crossing at Robertson’s Lick, Steigal fastened the head into the fork of a tree, where it remained for a long time, earning the spot the name “Harpe’s Head” (67).

The Last Harpe

Little Harpe successfully escaped and didn’t reappear for five years. The women were captured where they were found in the valley and were made to stand trial for their association with the Harpes. The Court acquitted them, and they were bound over to jail to be protected by the warden, Major William Stewart. The three Harpe women eventually married and lived respectable, relatively comfortable lives—they outlived Steigal and both Harpe brothers (67-69).

In 1802, about five years after Big Harpe had been killed, word of Little Harpe resurfaced when William C. C. Claiborne, the governor of the Mississippi Territory, sent out letters to the commanders of military outposts stationed along the Mississippi River and the Natchez Trace. These letters mentioned that Little Harpe apparently was part of judge and highwayman Samuel Mason’s gang, and soon rewards were being offered for Mason and his gang, including Little Harpe. He had flown under the radar for some time, and no one really knew what he had been doing until some of his actions were disclosed later at Mason’s trial (145, 146-149).

In the beginning of 1803, Mason—along with his family and an associate going by the name of John Taylor—were captured, and Taylor and Mason were put on trial. During the trial, Taylor said that his real name was John Setton and that he had been an honest worker doing odd jobs since he arrived in America from Ireland (156). He claimed that Mason had held him prisoner (157). Later, while being moved to Natchez where the trial was supposed to continue, Mason, his family, and Setton escaped. It was only when Setton arrived in Natchez with a man named Samuel Mays, carrying Mason’s head in a clay mold and seeking to claim the reward, that people recognized Setton as Little Harpe. They proved it was him by identifying a scar on his chest (162-163).

Harpe and Mays tried to escape but were recaptured twenty miles north of Natchez in Greenville, where they were put on trial and sentenced to death. They were hanged on February 8, 1804, and their heads were then cut off and mounted on poles along the Trace to serve as a warning to other outlaws (163-164).

Like many other tales of outlaws, pirates, and highwaymen, the bloody journey of the Harpes came to a violent end. No one will ever know the full motivations behind the Harpe brothers’ malice and brutality; whatever the reason, be it madness or greed or both, their terrible exploits left a legendary mark on the areas along the Natchez Trace.

Source

Coates, Robert M. The Outlaw Years. New York, The Literary Guild of America, 1930.

Murrell: A Malignant Mastermind

Note: The following account comes from the book The Outlaw Years by Robert M. Coates. His record of the lives of the outlaws and the events surrounding the Trace is not a complete, infallible account given his artistic embellishments, more recent discoveries, and the difficulty of distinguishing historical fact from folklore. However, the book holds much significance since Eudora Welty used it as a reference for her stories, and thus the information within it is valuable not only for its historical account but also for its usefulness in examining her writing.

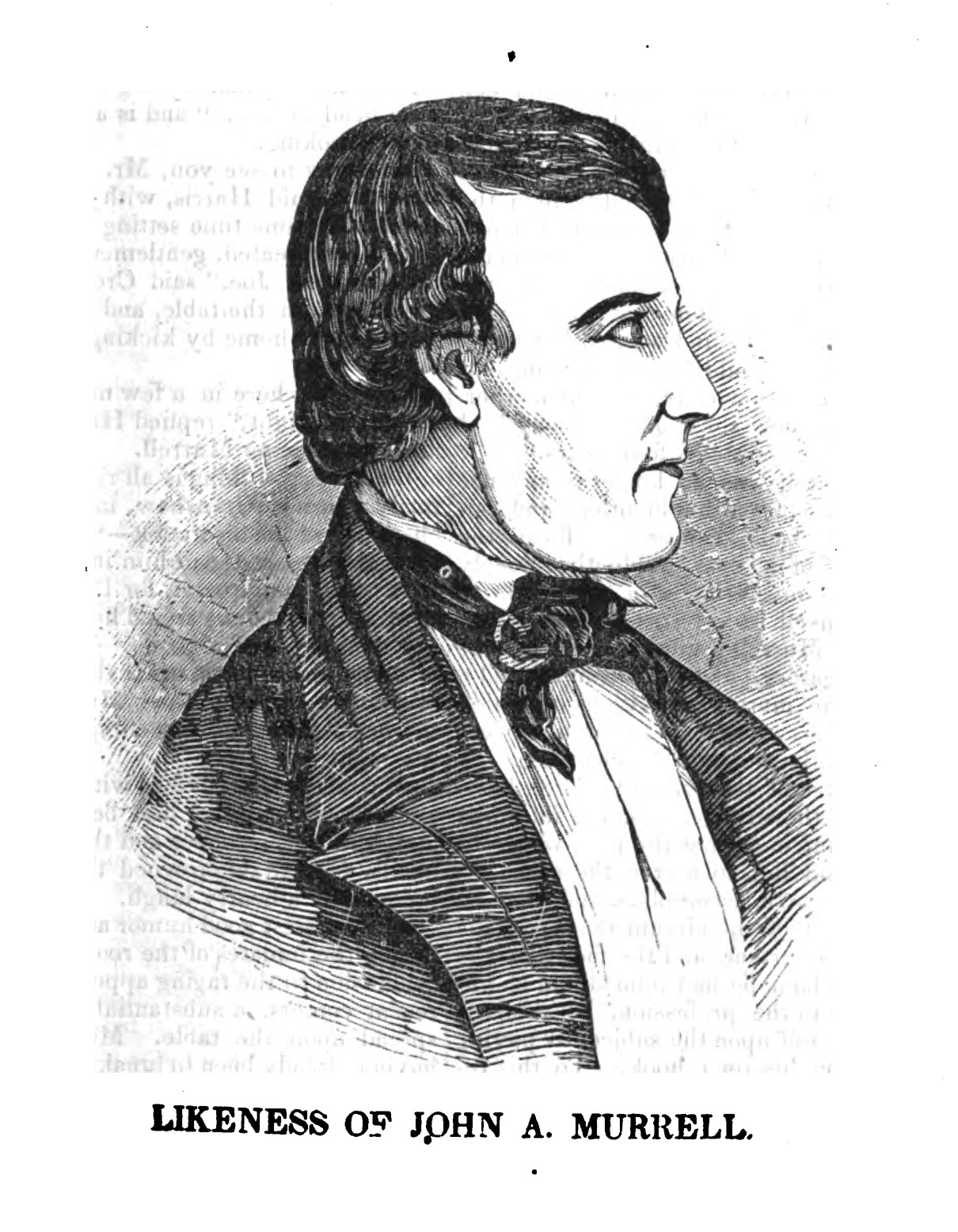

Foreboding Beginnings

John A. Murrel’s exact birthplace is unknown, but he was born in 1804 somewhere in Tennessee, likely near Columbia, a town located on the Natchez Trace fifty miles south of Nashville. His father owned a small tavern on one of the trails of the Trace (Coates 206). According to Murrel, his father was an honest, hardworking man. His mother, however, engaged in criminal activity and taught Murrel and his siblings from a young age how to steal. She was left in charge of the inn, and when Murrel became good at picking locks and stealing—at about ten years old—he would sneak into the guests’ rooms after they fell asleep and take some of their belongings (207).

From one guest, a peddler, Murrel stole a bolt of linen and some other things. Later, at about sixteen, he stole fifty dollars from his family’s savings and traveled to Nashville, where he accidentally ran into the same peddler he had stolen from years earlier.The peddler was actually a highway robber, a pirate, and a murderer named Harry Crenshaw. He talked with Murrel, and they headed east together along the Wilderness Road to deliver some stolen horses in Georgia. After, they headed for New Orleans by way of Alabama (207-210).

Until the state of Alabama was admitted to the Union in 1819, Spain strongly argued against America’s claim to southern Alabama. Even after the state’s admission, the territory still experienced lots of unrest. Rumors spread in one town of a slave uprising. As in many towns, the number of slaves was much greater than the number of whites, so the latter panicked at the hint of such rumors. By the time Murrel and Crenshaw arrived, few people could be seen out and about except the armed guards patrolling the streets, and a curfew had been placed for slaves. As a result, the two outlaws were able to steal from the store and some passersby for a couple days before leaving the town, and the crimes were blamed on slaves. Supposedly, the occurrences in that town inspired Murrel to begin formulating an idea about a countrywide slave rebellion that would allow him to loot on an even greater scale (211-212).

Murrel, to avoid suspicion and evade accusations, studied law, got married, and made many friendships. He often disguised himself as a minister while traveling, and he used this ruse to distribute counterfeit money or while selling slaves he had stolen. Murrel would often help a slave escape from a plantation with the promise of freedom, only to turn around and sell the person in another town. He would do this repeatedly under the guise of helping them move further from the dangerous slaveholding territory, but when too many rewards and notices appeared concerning the escaped slaves, Murrel would kill them (225-226).

Meanwhile, his organization of allies and fellow outlaws grew in number and reach along the Natchez Trace. At Murrel’s headquarters, located near a Shawnee village in Arkansas along the Mississippi River, his men met and planned, hid themselves and stolen slaves, and kept counterfeit money and stolen goods. Murder and robbery were prevalent, and in many of the towns, the law was ineffective; many sheriffs, juries, witnesses, etc. were either bribed or threatened. Murrel’s affable and gentlemanly manner allowed him to pass through many towns without much suspicion (229-230). Murrel also gained acquaintances through his supposed opposition against slavery; he is said to have connected with many abolitionists from the North (237).

In 1832, he was arrested in Nashville for stealing a mare. He was convicted and sentenced to a series of punishments, including twelve months in prison. While in jail, he developed his plan further. In this plan, which came to be called the Mystic Confederacy, Murrel decided that he would gather an army of escaped slaves commanded by outlaws with himself at the lead and incite a widespread rebellion of killing and pillaging. He sought to turn the territory into a lawless pirate kingdom that he would rule over (238-240).

Murrel gathered his friends at a house in New Orleans, where they constructed and agreed to a plan. In preparation for the coming scheme, Murrel instituted a hierarchy of command, mapped out the prospective territories for his kingdom, sent people to covertly speak with slaves, held regular meetings, established lines of communication, and formulated battle plans. Natchez was to be the first victim of the rebellion, after Murrel had organized about 380 allies under his command and set the first date of attack for December 25, 1835 (241). Murrel’s scheme was quick to derail, however; after stealing two slaves from a Parson Henning, he met a man named Stewart along the trail, and Murrel told this man his plan and incited his own downfall (242).

Virgil Stewart, False Outlaw

Stewart was originally from Georgia. His father died when he was young, and his mother basically left him to his own devices. He traveled west, worked on several plantations, and finally settled in Jackson, MS. He met Parson John Henning and his wife in Jackson, and he grew very close to the Hennings.

During one visit with them in January 1834, they informed him that someone was stealing their slaves, and that they suspected a man named Murrel. John Murrel, having come from an area near Memphis, recently settled in the region on a large farm. He had a wife and younger brother, as well as a dubious reputation. Murrel had learned of the Hennings’ suspicions of him and had sent them a letter in attempt to reassure him of his conduct and good intentions, as well as invite them to investigate him after his return from a business trip to Randolph, Tennessee (175-176).

Stewart decided to help the couple and investigate Murrel himself. Stewart rode out to the small town of Denmark to wait for Murrel to pass by on the nearby trail. When Murrel finally did pass by, Stewart followed and caught up to him a couple miles farther down the Trace.

At first, Murrel was reluctant to chat with Stewart after Stewart greeted him. But, Stewart persisted, posing his conversation so that he showed a little sympathy to those who went beyond the law. He joked with Murrel too, and the man finally began to relax. Murrel allowed himself to be flattered and, with an air of arrogance, began to tell Stewart of his deeds, thinking he was fooling Stewart by framing these stories in third person. Stewart too gave himself an alias. While Murrel talked, Stewart scratched notes of names and dates into his saddle, and whenever he found time alone when they stopped, he wrote notes in a notebook he carried with him. He gathered the details of Murrel’s criminal activity, including his plan to build a pirate empire out west (178-180).

Murrel invited Stewart to go with him to Arkansas, where the Clan’s headquarters were located. Stewart realized that if he said no, he would arouse Murrel’s suspicions. Stewart agreed to go (189-190). Murrel also finally told Stewart his real identity (191-194).

Murrel told Stewart about the Mystic Conspiracy and the so-called “Clan” he had gathered, saying there were about four hundred top officials in the Grand Council and six hundred and fifty members in the “strykers” group, who were in charge of the dirty work. Murrel believed that the Clan would have at least two thousand members by the time they began their attack in December (244). Murrel also informed Stewart that he wanted Stewart to be with him in New Orleans when the rebellion began; he apparently planned for the rebellion to begin at the same time in various locations, moving down the river to encompass the territory (245).

They had some difficulty crossing to Arkansas due to flooding. At last, they came to the headquarters, which consisted of a large log building. Stewart learned that the Hennings’ slaves had been sold after one of the Clan members took charge in Murrel’s absence. Stewart was also initiated into the Clan and taught the secret hand signs. Later, he came up with an excuse to leave, saying he would meet back up with Murrel at Mr. Irvin’s plantation, one of the places they had stayed while trying to get to the headquarters. Murrel had arranged to purchase some slaves for Irvin and deliver them in a couple weeks (250, 254). When Stewart made it back across the river, he stayed with Irvin for the night and told the man what was happening. Irvin agreed to have someone hidden in the house waiting for Murrel when he arrived with the slaves. The next day, Murrel rejoined Stewart, and they rode to Wesley, where they went their separate ways. Murrel gave Stewart a list of almost one hundred names of clansmen. Stewart headed south for a couple miles since he told Murrel he was heading to Yalobusha, but he then turned east to get ahead of Murrel on the way to Madison (255-256).

End of an Empire

When Murrel arrived at his plantation home in Madison three days later, he was arrested and questioned. The farmers in Madison had decided to take matters into their own hands rather than wait for Murrel to be captured with stolen slaves in his possession at Irvin’s plantation, and it became Stewart’s word against Murrel’s. To gather more evidence, Stewart and a posse searched the headquarters, looked for the slaves that had been sent to the market, and placed guards at Irvin’s house, but with no success (256-258).

After Murrel sent word to his Clansmen that Stewart had a list of many of their names, many of which belonged to prominent figures in society, a widespread effort began to damage Stewart’s character so his testimony would be ineffective. Stewart had moved around frequently throughout his life, and he did not have many connections, making it even easier for people to spread rumors about him. Murrel wrote a letter informing his colleagues on how to damage Stewart’s character and prove that he sought to profit personally from Murrel’s arrest. He sought false witnesses to sign the letter saying they had seen Murrel and Stewart together and that Stewart told them he was being paid for apprehending Murrel (258-260). While waiting for the trial to commence, Stewart even uncovered plots concerning people who had been sent to kill him (258, 262-268).

In July 1834, Murrel’s trial was held in Jackson, MS. Murrel was defended by a capable and intimidating lawyer named Milton Brown, who fervently attacked Stewart’s testimony to discredit him. Stewart was the main witness for the State, and he read his entire journal record of Murrel’s conversations with him, including the co-conspirators’ names Murrel had given him. Ultimately, Brown’s efforts failed, and Murrel was found guilty of stealing slaves and selling stolen slaves. The court sentenced him to ten years of hard labor in the Nashville State Penitentiary (268-270). Murrel’s wife moved out of the territory, and his friends disappeared (272).

Stewart also left town, planning to go to Lexington, Kentucky. He reached Lexington and was able to find safety there. He published a pamphlet detailing his entire experience, but it failed to carry the sincerity and gravity he hoped. No one really felt threatened by Murrel anymore, and many people did not believe in Murrel’s conspiracy. Also, some of the rumors that had arisen during the trial to discredit Stewart stuck with him, further dampening belief in his account (272-274).

Murrel served out his term in the Nashville State Penitentiary. During his time there, he first studied law and then the Bible, and he planned to be a minister when he was released. However, he suffered some sort of mental decline or breakdown before being set free. It is unsure what really became of Murrel after he was free. His family had moved away or disappeared, and his lands had been claimed. What became of him at the end of his life is unknown, as he too vanished somewhere in the territory (301).

For many who had put their faith in Murrel’s outlandish scheme, their efforts of secrecy and crime culminated at the end of a noose. Remnants of the Clan survived after Murrel’s imprisonment, though they struggled to organize and coordinate. Ultimately, the Conspiracy lacked adequate direction and only manifested itself in scattered fights and uprisings that did not seem to be connected, especially since animosity was brewing at this time between different groups of people in the territory (274-275). However, some towns did hear of the conspiracy and engaged in frenzied efforts to investigate and prevent an uprising. In Livingston, for instance, a so-called Committee of Safety was organized that had the power to question and try people suspected of being a part of the conspiracy (283-284). During this committee’s operation, a significant amount of slaves as well as implicated white citizens were questioned, tortured, and hanged. A man named Joshua Cotton was brought to trial, and he eventually revealed that he was a member of the Grand Council of Murrel’s Clan, and that they still planned to incite an uprising. The Committee of Safety hanged Cotton after he confessed in order to send a message to the other Clan members (286-287). Laws and law enforcement were strengthened, and widespread efforts were undertaken to eradicate the large numbers of criminals, gamblers, highwaymen, etc. around the territory (298). The dream of a criminal empire faded into the past with the outlaws who had pursued it.

Source

Coates, Robert M. The Outlaw Years. New York, The Literary Guild of America, 1930.

Technical Credits - CollectionBuilder

This digital collection is built with CollectionBuilder, an open source framework for creating digital collection and exhibit websites that is developed by faculty librarians at the University of Idaho Library following the Lib-Static methodology.

The site started from the CollectionBuilder-GH template which utilizes the static website generator Jekyll and GitHub Pages to build and host digital collections and exhibits.